“Everyone has a story. It might or might not be a love story. It could be a story of dreams, friendship, hope, survival or even death. And every story is worth telling. But more than that, it’s worth living.”― Savi Sharma, Everyone has a story

Dear School of Thought Readers,

The other day, I was sitting on a bench in the park near my home, writing my book in my head. I am constantly doing this lately, going outside to process. The weather was perfect (unlike this week) and everyone was outside.

A few minutes in, two men sat down at the other end of the bench. One was mid-thirties, the other was older, white-haired, wearing what looked like an entire outfit made of linen. They didn’t look like a matched set. I love to eavesdrop, so my story, from what I could gather sitting there next to them on the bench, was that they were son and father-in-law.

They were playing that game you play when you're killing time with someone you don’t quite know what to say to: the “people-passing” game. A stranger walks by, and you build fiction around them, what they do, what their secrets are, what they’re carrying in that overstuffed tote bag. It’s a kind of joint storytelling.

And here’s this unlikely pair, I think the father- in-law was British and he was there with his slightly overeager sporty American son-in-law building these stories out of thin air. And they’re good at it. Really good.

I sat there pretending to read, but really, I was eavesdropping. Because this moment was reminding me of all the unknown stories living around us every day.

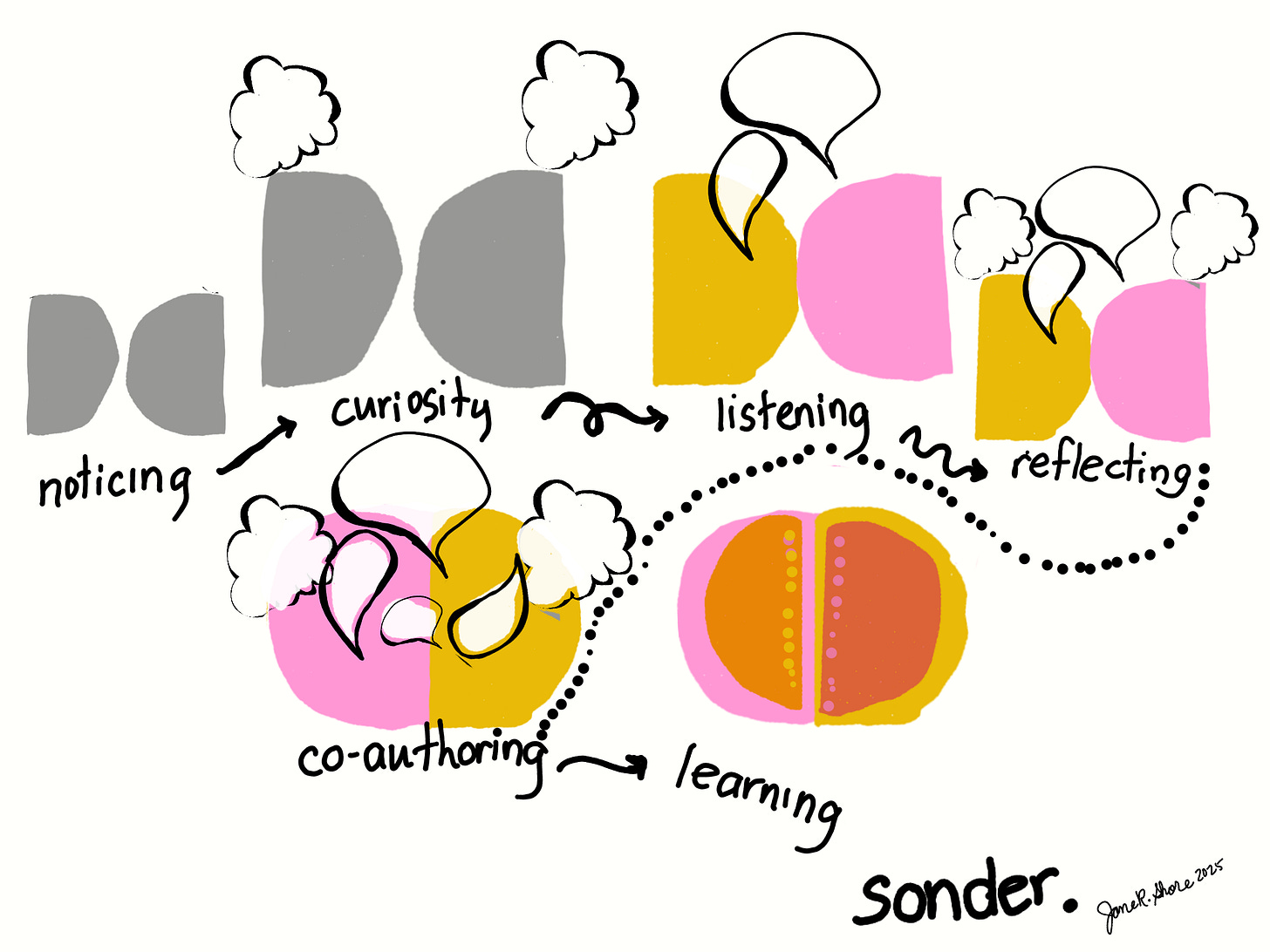

There is a word that gives a name to that feeling: sonder.

It was coined a few years go by John Koenig in The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows.1 It was later surfaced in Joe Keohane’s book The Power of Strangers.

Sonder: the realization that each random passerby is living a life as vivid and complex as your own.2

Joe Keohane described this as sad, like discovering secrets you may never know. But then in a podcast, UPenn prof Adam Grant reframed it.

Instead of seeing sonder as missing out, what if we saw it as an invitation?

The Big Idea

What Adam Grant did was transform the essence of the word sonder from scarcity to abundance. And when we engage with strangers, it’s not just stories. We change.

In his book The Power of Strangers, Joe Keohane shows how talking to people we don’t know sharpens our thinking, stretches our empathy, and challenges our assumptions.

So I've been thinking about this idea: A sonder mindset is the practice of recognizing we all have untold stories, and at the right time, in the right place, that means there is something to learn in everyone.

Holding a sonder mindset is a shift from asking, “How do I get this person to understand me?” to, “What might I not yet understand about them?”

This makes me think of a recent trip my oldest and took.

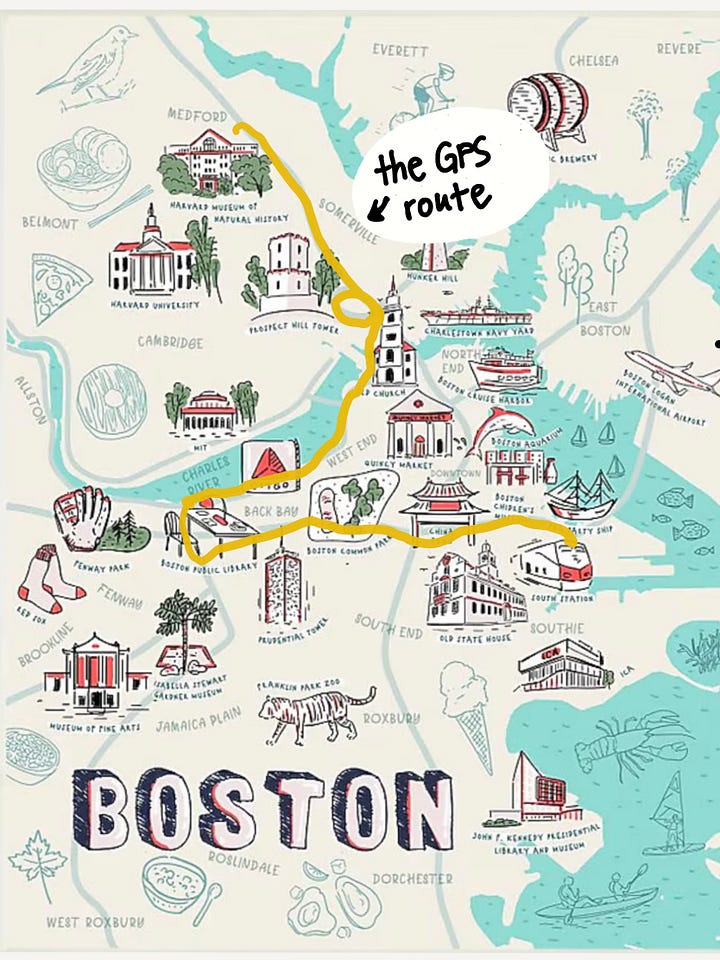

A few weeks ago, my son and I were in Cambridge, Mass, about to miss a train.

We had called an Uber to South Station, where our train to Philadelphia was set to depart in exactly twenty minutes. The GPS, with a precision I normally love, told us the ride would take twenty-four. It didn’t look good.

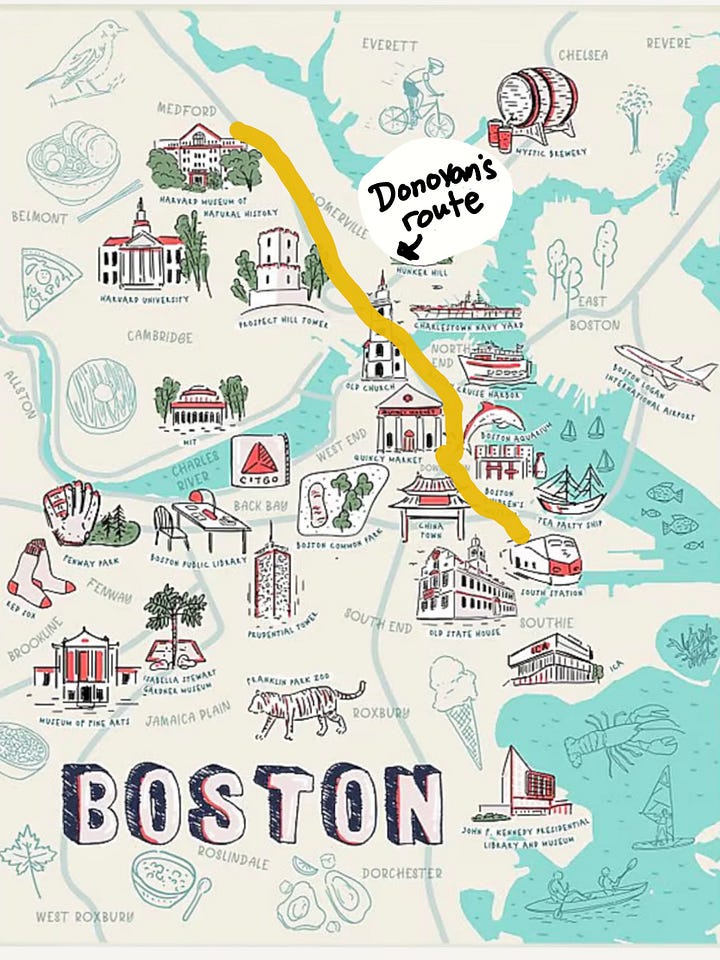

Our driver was a man named Donovan. He was wearing sunglasses despite the clouds, and reggae was playing softly on the stereo, Bob Marley, something from Exodus. We told him we were late. Without even a hint of panic, he turned to us and said, “Don’t worry, we will get there.”

Now, this might sound like bravado. But it turns out it wasn’t.

Donovan was born in Jamaica, but had been in Boston for nearly two decades. He knew the back streets, and he was taking them. As he began weaving, ignoring the GPS entirely, he also began telling stories, about his mother in Kingston, his daughter who was starting college, and his belief that there’s always a shortcut, if you know where to look.

We watched the time estimates get shorter and shorter.

We made it in seventeen minutes.

As we hopped out of the car and dashed toward the train, yes, we made it, Donovan gave us a wave, a smile, and disappeared back into the flow of traffic.

My son, still catching his breath, turned to me laughing:

“Mom, how did you learn that guy’s whole life story in twenty minutes?”

But maybe the question is really: How much can someone reveal in twenty minutes, if you’re paying attention?

The answer, I think, is more than we realize.

While the moment was dramatic, learning his story, with the music in the background as we wove through small streets in Boston (and watched the time go DOWN!) … we were learning.

Sonder begins with noticing. And getting a bit curious.

And I recognize that in listening, we became part of the story, too.

When we ask questions, and actually hear the answers, we don’t just collect stories, we shape them. We become part of the learning and the teaching. And sometimes, we even help people tell their own stories better, more fully, more clearly, more courageously. (I find that speaking to some people I say things I didn’t realize I thought…it’s like their presence helps me think.)

So maybe we try again. It’s not just: How much of a life can someone reveal in twenty minutes if you’re paying attention?

But also: What might happen if we help someone else discover the story they didn’t even know they were ready to tell?

In that way, storytelling becomes a kind of learning. And storylistening becomes a form of service

.

Making Big Ideas Usable

Sonder doesn’t have to be fleeting. It can be a way of moving through the world, a way I am appreciating more and more.

It’s slower, more curious, more reverent.

Donovan didn’t just get us to our train. He gave us a glimpse into a life that might otherwise have gone unnoticed by us. And that might be the secret: noticing isn’t passive. It’s participatory.

What if sonder isn’t just a concept, but a practice? Sonder is more a way of walking through the world.

Maybe we’re not meant to know everyone’s story, but to remember that there is one.

In my own work, I’m exploring how to help people find the story in their experience. I think it unlocks learning, growth, and sometimes even healing. Whether through a drawing, a workshop, or a post like this, part of my own sonder practice isn't just listening. It’s lifting.

I’m building a self-syllabus around how to be a better story-finder, story-listener, and story-sharer.

I am sharing some of the books I am loving below. I’d love to hear your list.

Recommended Reads

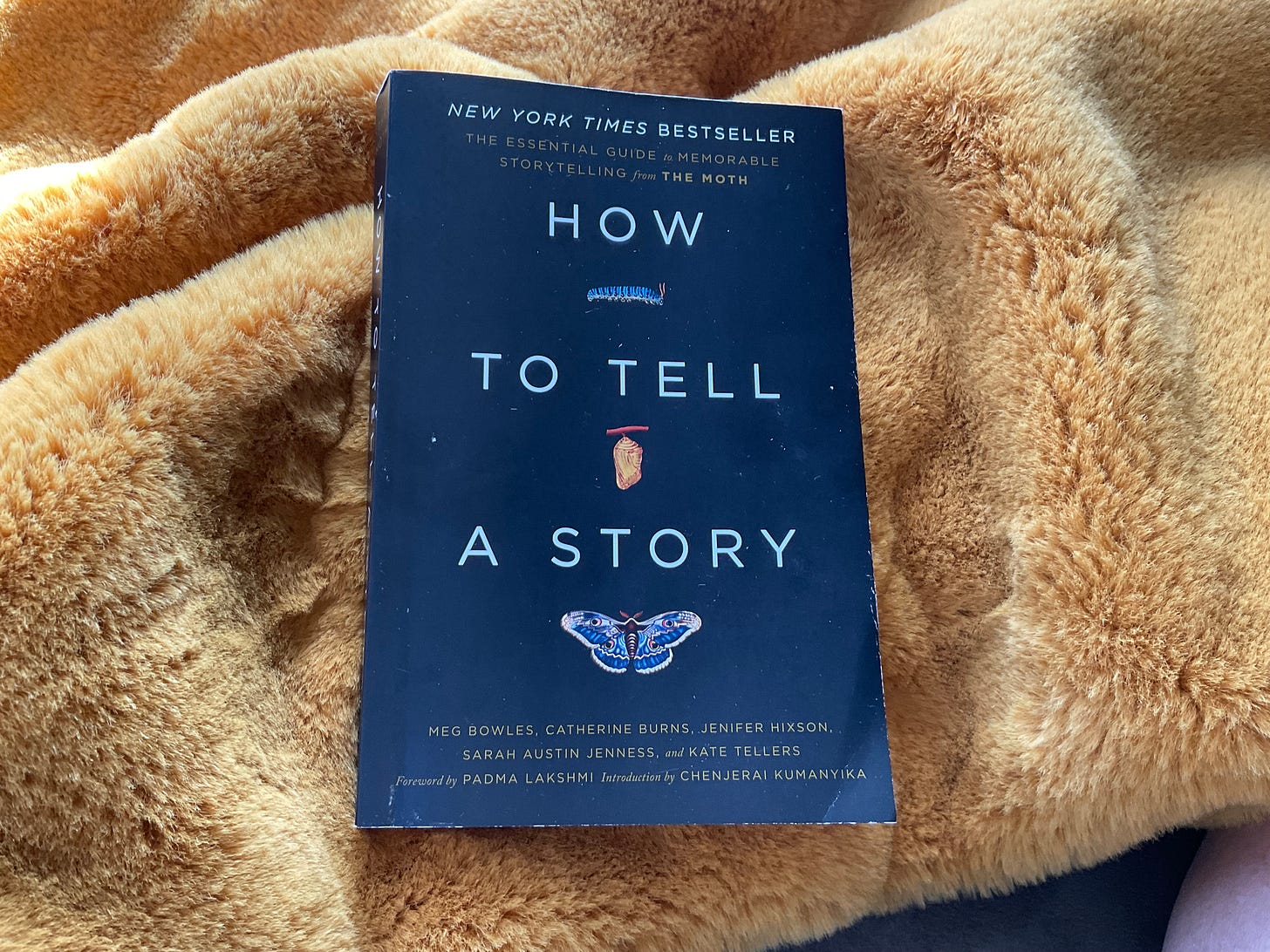

My friend, writer

, just shared the most thoughtful gift with me ~ How to Tell a Story (2022). ❤️ I am already halfway through and loving it. It's so engaging, and examples are drawn from live audience performances at Moth gatherings. There are gorgeous and relatable "how tos” on what to do and what not to do. It pairs well with The Power of Strangers ⬇️. Perfect writer's reference guide. Highly recommend!

The Power of Strangers (2021) by Joe Keohane – A warm, smart exploration of how talking to strangers transforms us. ❤️ stories throughout. * Pairs well with How to Tell a Story.⬆️

The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows (2021) by John Koenig – For poetic redefinitions of complex emotional experiences. On my bedside table rn.

Hidden Potential (2023) by Adam Grant – Especially the chapters on how our environment and interactions shape our growth.

The Extinction of Experience (2024) by Christine Rosen- Explores what we lose (connection) when we trade real-world connection for digital convenience.

Draw Your Adventures (2025) by This one is soon to be published, but all of her books remind me of my own childhood. I grew up in an house of artists, always drawing wherever I was. Stories don’t need to be written or told, they can be drawn. There’s a story in that.

The world is overflowing with hidden teachers, and unexpected classrooms. Sonder is not the sadness of what we’ll never know. It’s the thrill of what we might still learn.

How would our questions change if we believed everyone had something to teach, and we needed to find ways to bring out those stories and share them?

He writes of the Dictionary, “Each original definition aims to fill a hole in the language — to give a name to emotions we all might experience but don’t yet have a word for. All words in this dictionary are new. They were not necessarily intended to be used in conversation, but to exist for their own sake.”

Wiktionary says this: “Coined in 2012 by John Koenig, whose project, The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows, aims to come up with new words for emotions that currently lack words. Inspired by German sonder- (‘special’) and French sonder (‘to probe’).”

Very interesting post! I often do this with my partner. You raise an extremely good point though, to take Sonder one step further and truly listen to these peoples stories.

In England, there's often quite a lot of older men who sit in pubs from the second they open until near closing time, they'll happily talk to anyone. I think it's part loneliness but part intrigue. They've learnt that all the best stories come from the people that are surrounding you every day, you just have to ask.

Very thought provoking! I discovered you quite by mistake - joining Substack to view an art video! Sonder is a new word for me - off to do some research! Thanks for your insights.